Repeatedly referred to in the press as “massive,” the Google Docs attack which has been the talk of the security blogosphere and even mainstream media this past week appears to have sent invitation emails to an estimated “less than 0.1%” of Gmail users, according to Google’s own statement, which is not a particularly massive fraction. Although that still could signify one million users — but in terms of sheer volume, it’s not a lot compared to billions of ransomware emails being pumped out by a botnet in a single day. So why all the excitement?

Using the Legit to Lull You

From the distance of a week, we can consider the attack a bit more calmly. Besides the association of Google’s brand, what drew everyone’s attention was the fact that the fundamental misdirection at the heart of the attack was the use of a legitimate app access process, giving it all the feel of a normal routine. The attack really brought home for many how clever the “bad guys” can be at disguising their schemes, creating a sort of augmented reality which is difficult for the average user to distinguish from the real thing as they go about their routine. And further underlines the limits of training users to police their activities, and the importance of intelligent systems in securing Internet activity.

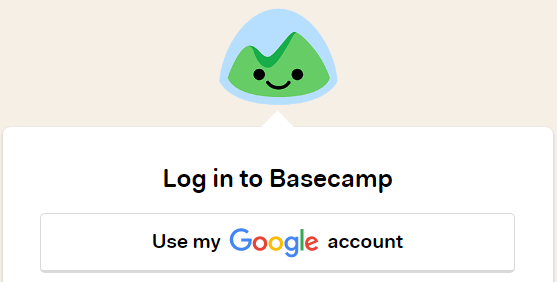

If you are a Google user, have you ever signed up for an online service and been given the option to “use my Google account”? As a completely unrelated illustration, let’s say you wanted to sign up for a legitimate service like Basecamp (online productivity software). First you click on “Use my Google account”:

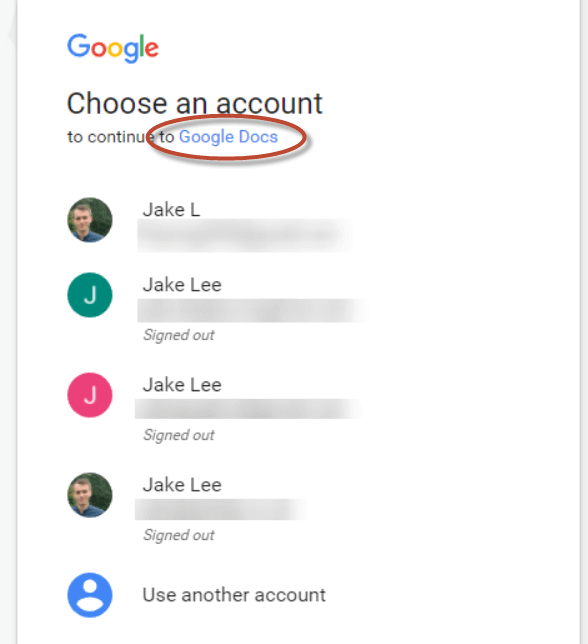

And next you choose the Google account that you want to use.

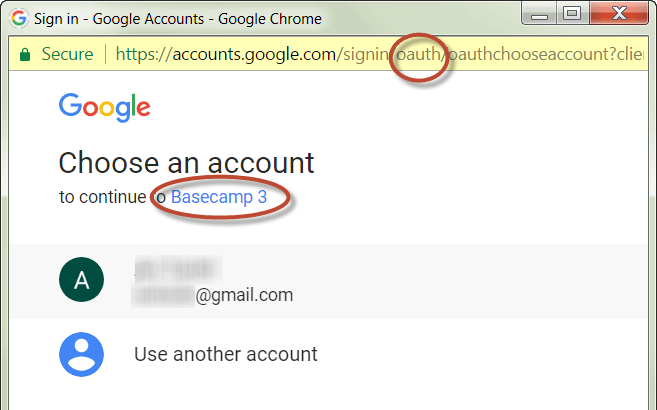

Notice that the login uses OAuth at accounts.google.com (shown in the yellow URL bar at the top of the screenshot above). OAuth 2.0 is the protocol used by Google to give 3rd party applications access to Google services – in this case Basecamp gets access to your Google ID. Also notice that the imagined victim is choosing from one of their user accounts “to continue to Basecamp 3”.

Applying the logic of this example to this attack, the user wouldn’t be continuing to the real Basecamp 3 – they’d have just gone through a totally legitimate Google process with the end result of approving a malicious app.

How It Really Works

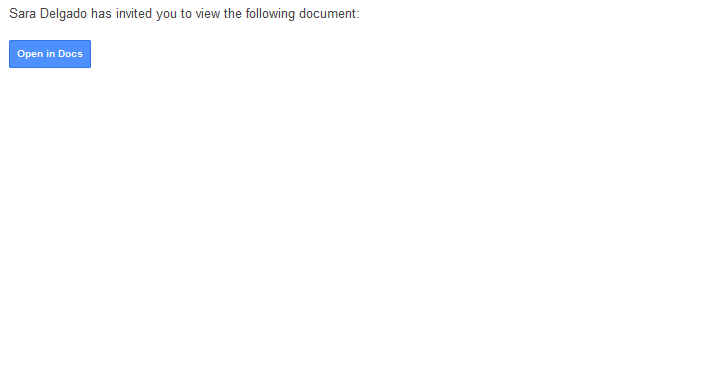

This specific attack starts with an email, apparently from someone you know, and an invitation to click on a link to a Google document, as shown below. In the emails, the attackers used a common method of replacing the “To” field with the spoofed email address “hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh@mailinator.com”, while adding the victim’s email to the BCC field. The emails were sent in the name of prior victims who had fallen for the attack.

After clicking to open the doc, the victim is prompted to choose an account and continue to “Google Docs”.

It feels quite safe to the typical user — after all, you’re in a Google domain accessing “Google Docs” – however, in the case of this attack, it wasn’t Google Docs at all, hence the quotation marks around the name. The attackers simply named their malicious application “Google Docs”.

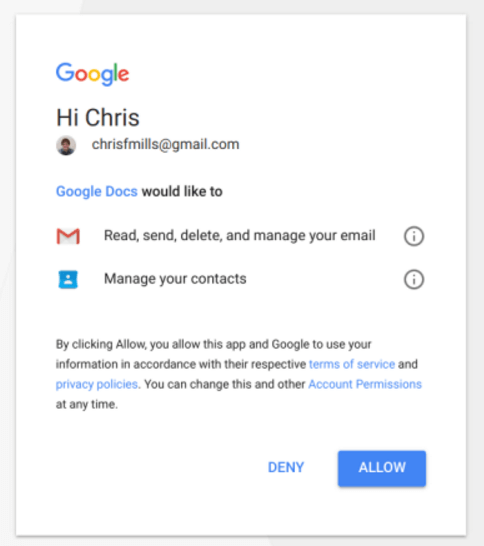

Once a user chooses a Google user account, they are presented with an option to allow the app to access email accounts and contacts, shown below – effectively allowing the quick spread of the invitation email to their contacts, and so on.

A Phishing Attack or a Worm?

So the attack is perhaps more accurately described as a worm — not purely a phishing attack as widely reported. (For a definition of what is and isn’t “phishing,” download Cyren’s special threat report on the topic.) Of course, once criminals have gotten access to your account, they might be able to use the data in your Gmail or Google+ accounts to search for passwords and credit card numbers, or leverage the data in your account for follow-up phishing scams with your contacts. But in this specific case, since there was no actual solicitation of or stealing of credentials per se, so it doesn’t meet a purist’s definition of phishing.

Quick Google Response Hides Endgame

We are also left to speculate a bit as to the attackers’ ultimate objective, since the attack appears to have been stopped quickly and perhaps before reaching full maturity. A Google staffer who was reading the Reddit forum where the attack was first mentioned forwarded the details to colleagues at Google, and the bogus “Google Docs” was shut down within an hour. Having obtained contact information, we can speculate that the attackers could:

- Harvest your contact info and use the combination of contact names and email addresses to send more targeted fraud or phishing emails

- Search for password confirmation emails

- Perform password resets on accounts at other sites using your email address

How To Stop It: Early, Often, and Across Web and Email Channels

Google followed up the quick takedown with this message: “…we’re taking multiple steps to combat this type of attack in the future, including updating our policies and enforcement on OAuth applications, updating our anti-spam systems to help prevent campaigns like this one, and augmenting monitoring of suspicious third-party apps that request information from our users.”

There was widespread speculation about ways to prevent such applications being registered in the future. It is generally agreed that simply blocking the name “Google Docs” in the OAuth environment would not be enough — since Unicode characters can be used to easily create variations that will appear to users as “Google Docs” (see our article on Unicode abuse).

In addition to having robust web and email security inspection — including specifically businesses using corporate Gmail accounts should consider adding cloud-based gateway security — users should maintain a “guilty until proven innocent” outlook on any request to click on anything, and can run through the following checklist for any email they receive:

- Was it sent to me?

- Do I know the sender?

- Am I expecting such an email from this sender?

- Is the info in the original email header consistent with this information?

- Am I being redirected to an outside site and then asked for any passwords or permissions?

In the case above, the real Google docs should not have had to ask for permission for access to Gmail.

Users who want to review third party apps connected to their account can visit Google Security Checkup.

To run a quick check of your overall web security posture, try Cyren’s Web Security Diagnostic